The long-term care and intermediate care sector covers services provided by residential nursing/care homes and care provided within your own home. This is a complicated area where care provided free under the NHS meets means-tested care provided by social services. After over 30 years of a policy of privatisation in this sector, service provision is almost exclusively by the private sector, with only a small amount provided by local authorities and the not-for-profit sector.

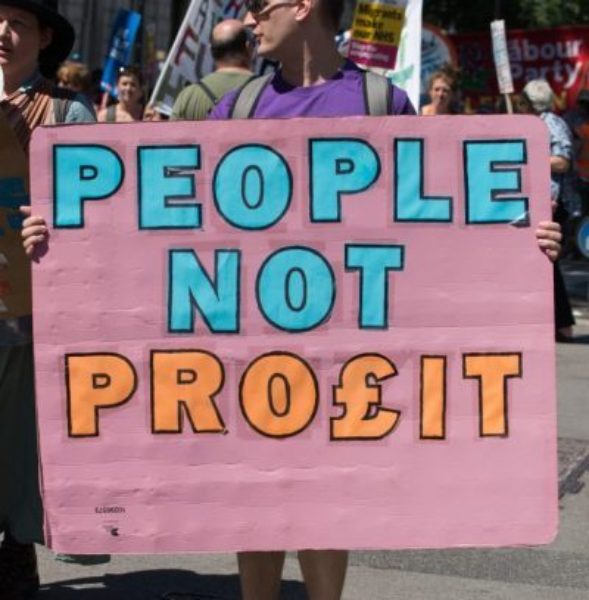

The privatisation of social care was supposed to lead to better care and more choice for people; what it has led to is a system of declining care standards, widespread financial instability, poorly paid staff, and money siphoned off to tax havens. The long-term care system is on the brink of collapse and one could say that the entire system is an example of a massive contract failure. More details can be found on our Sector overview of Long-term Care.

In March 2022, Care England CEO Professor Martin Green OBE warned that the country had reached a “pivotal point” in determining the future sustainability of adult social care, adding the government’s plan for reform was “largely underfunded”. He called on Chancellor Rishi Sunak to address social care underfunding ahead of the Spring Budget on 23 March 2022; social care underfunding was not addressed.

The government has announced that £5.4bn to be invested in social care over the next three years, funded by the new Health and Care Levy, but Professor Green noted that this would not be enough to achieve the government’s ambitions, and was dwarfed by the £36bn allocated to the NHS.

It is difficult, however, to reconcile an industry whose leading companies are paying directors millions, and making large profits for hedge funds and private investors, often based overseas, with one that is justified in receiving more money from taxpayers.

Financial melt-down and workforce crisis

Funding for this sector was a major target of austerity policies and continued reductions in funding of local authorities means that providers are facing financial melt-down and a workforce crisis. The level of privatisation in this sector means that local authorities and NHS organisations have very little control over service provision and if companies go bankrupt or decide to leave the market, all they can do is pick up the pieces.

One of the most well-known contract failures in long-term care, was that of Southern Cross in 2011. Southern Cross was a large national care home provider which had 9% of the market nationally, although within the northeast, Southern Cross accounted for around 30% of all care home places. The company’s collapse risked the care of 37,000 people. Its collapse has been put down to factors all related to the fact that as a private company it needed to make a profit. The company’s finances involved a complex mix of creditors, property investors, bondholders, banks, shareholders and landlords and the think-tank CHPI notes that as the company struggled with debt and a reduction in income there was “a reduction in property maintenance, which in turn led to lower occupancy; loans attracting higher interest rates because the company no longer had properties against which to secure loans; a fall in market confidence and the share price; and poor management and quality of care, which led to adverse inspection reports and further decreases in occupancy levels.” As it was a private company, the local authorities had no control over the situation, all they could do was try and pick up the pieces after its final collapse.

In March 2017, an investigation by OPUS, Company Watch and BBC Panorama found that care firms have cancelled contracts with 95 councils, saying they cannot deliver services for the amount they are being paid. The research also found that 69 home care companies had closed in the preceding three months and one in four of the UK’s 2,500 home care companies is at risk of insolvency.

In March 2017, Mitie sold its home care division to specialist healthcare investor Apposite Capital for just £2; Mitie bought the division for £111 million in 2012. Mitie blamed cuts to payments by local authorities and the increase in minimum wage.

In November 2018, the CQC issued a report on the financial status of Allied Healthcare, one of the UK’s leading homecare providers; Allied Healthcare was due to make a large loan repayment at the end of November 2018 but there appeared to be insufficient funds. The report noted that the company might not continue trading after the end of November 2018. A letter to all councils and CCGs advised them to make contingency arrangements in the event of the company withdrawing from contracts.

Allied Healthcare provides care and support to over 13,000 elderly and disabled people in their homes. The company’s Primecare subsidiary has contracts for out-of-hours and urgent care throughout the midlands. CCGs and GPs have been sent letters advising them to find new providers of these services by the end of November.

Allied Healthcare is owned by German private equity investor Aurelius. In a statement the company said it was “actively exploring a range of options in order to minimise disruption to continuity of care, including the sale or transition of care and support services on a regional or contract-by-contract basis to alternative providers best placed to deliver care at a local level”.

The financial stability of the care home companies show no signs of improving. Private equity firms view social care as a lucrative market and have amassed huge amounts of debt buying up care homes. This could easily trigger a financial crisis that would leave local authorities to pick up the pieces, as with Southern Cross in 2011.

In March 2019, accountancy firm BDO reported that more than 100 care home operators collapsed in 2018, taking the total over five years to more than 400. Its report warned that as homes closed many patients would have nowhere else to go but hospitals.

In October 2019. the Guardian reported on documents leaked from the CQC on the financial state of Advinia, a company that had grown to 10th in the English care home market via the acquisition of 22 BUPA homes in April 2018. The CQC is concerned about the company’s cash flow and ability to pay its debts. In late August 2019, the CQC warned over 150 local authorities in England and Scotland that Advinia was not cooperating in a financial investigation and the CQC could not give the company a clean bill of financial health. The local authorities now have to decide whether to use the company as a provider or not. According to the leaded documents, Advinia is not cooperating with the CQC and there are also concerns about the “competency and capabilities” of Advinia’s finance department as the company has had four finance directors over five months.

With the sector facing financial problems, the quality of the care that they provide to residents has been found to diminish – the facilities deteriorate, staffing levels are reduced and additional ‘services’ for residents, such as outings and entertainment, are cut back.

Research by Which (click here for Infogram) showed that the care homes owned and ran by private equity firms were among the worst in terms of CQC ratings of inadequate or requiring improvement.

See below for further reading on contract failures.